DC Circuits: Electric charge in motion!

So many situations in nature and technology involve electric charge in motion. The movement of electric charge along the optic nerve from your eye to your visual cortex transmits the image of a turtle in the form of a coded electric signal. If it’s nighttime, you’re reading your iPad that operates by using very complex electric circuitry. Or you can use the simplest circuit, a battery connected to a lightbulb to illuminate the room and allow you to read Harry Potter. The battery causes electrons to move through the circuit. As these electrons move through the lightbulb, they transfer energy in order to make it shine!

So we will briefly look at the Physics of electric charge in motion! A current measures the rate at which charge moves through a conductor. Ordinary conductors have resistance to the motion of charge so we set up a change is potential energy between the ends of a conductor to produce this motion, voltage. Just like a block siding down a ramp when friction is involved! In circuits, the increase in potential energy is the source of an emf (electromotive force) with the most common form being the battery. Simple circuits involve a battery and one or more resistors. I’m it’s purest, an electric circuit is used to transfer energy from on place to another.

DYK? A bolt of lightning releases so much energy that it heats air to a temperature of 30000 degrees Celsius, stripping electrons from atoms causing the air to glow!! Some specialized species of fish, like electric rays are equipped with organic batteries that can unleash a burst of energy to stun prey or fend off predators!

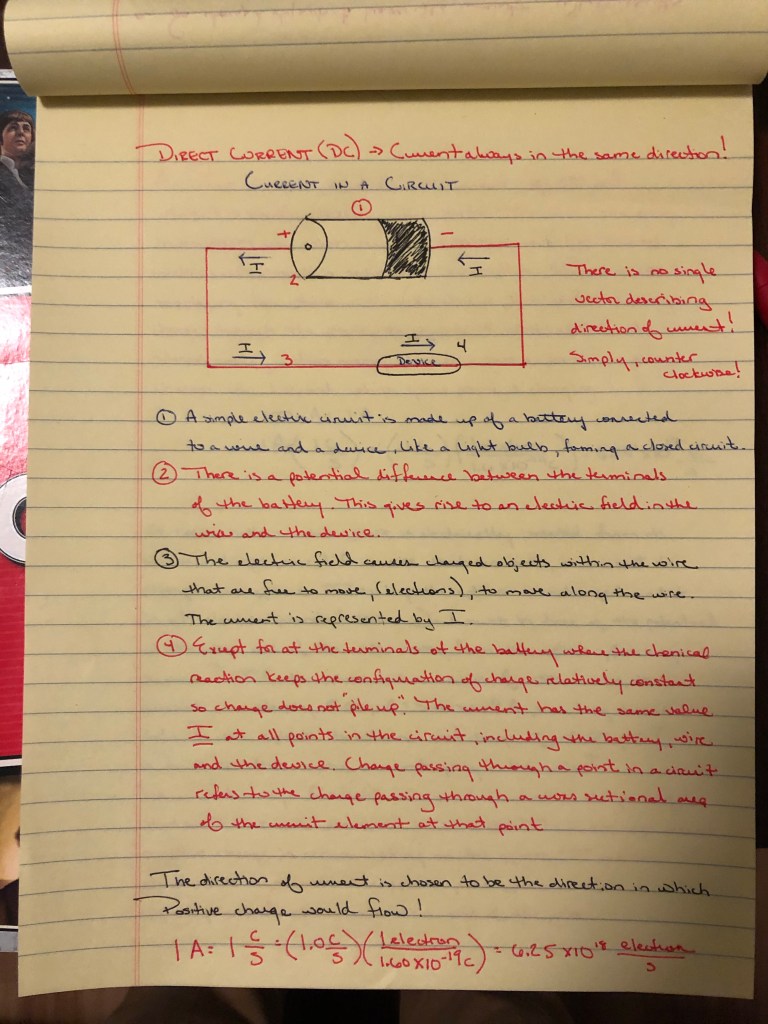

Electric Current is equal to the rate at which current moves!

So a battery sets electric charge carriers, electrons, in motion. A battery contains one or more electrochemical cells. Inside the cell are two different substances that, due to their different chemical properties undergo a chemical reaction so that each substance ends up with an excess or deficit of electrons. In the common battery, zinc ends up with the electron excess, manganese dioxide ends up with the deficit.

The terminals of a battery are each connected to one of the substances and electrons move between each substance. The terminal with the electron excess is the negative terminal and the terminal with electron deficit is the positive terminal. Because of the charge differential, the positive terminal has the higher electric potential. The potential depends on the substances and, for the aforementioned, it’s 1.5 V. A 9-Volt battery is made up of six 1.5 V cells.

In a closed circuit, where the wire makes up a complete loop, charge moves continuously from one terminal to another as if it were an object sliding down a ramp with friction near the Earth’s surface. Inside the battery, the chemical reaction “lifts” the charge back up to the top of the incline!

Current!!

Just like river, an electrons flow like water and an electric current is equal to the rate at which charge moves past any point in the circuit.

I = change (charge)/change (time)

The unit of current is the Ampere and 1 Ampere is equal to 1 Coulomb/s. We will say that the current has the same value at all times. This means electrons cannot “pile up” at any point except the terminals. Since charge is conserved, there is also no way for for more moving charged objects to join the current or for charged objects to leave the current. Whatever the amount of charge that moves into a point in the circuit, the same amount of charge must move out of the same point. The values of the current is the same around a closed loop! Current is not a vector but it does have direction, which is associated with which way positive charge would flow!

Resistance!!!

Electrical resistance can be found in every technological device, from the wires in an automobile ignition system to the resistors in a computer or mobile phone. What purpose does resistance serve? Well, the greater the resistance, the smaller the current, I. The resistance allows us to control the current due to any particular applied electric potential difference.

Resistivity, rho, depends on the material of which a wire is made a tells how well or poorly this material inhibits the flow of electric charge. For a copper wire, a good conductor of electricity, the resistivity is very low. For rubber, resistivity is high which makes rubber a poor conductor but a great insulator. Resistivity increases with temperature as heating increases disorganization and therefore collisions with electrons.

R = rho(L)/A

Ohm’s Law

Change (V) = IR

For a constant potential difference, such as a battery, across a resistor in a closed loop, the current will be the same everywhere in the loop. If you change the value of the resistance, then the amount of current will change compared to the original circuit but the current will still be the same everywhere in the loop!

We see this in every one of our cells!! In order for a cell to live, there must be a higher concentration of positively charged K+ ions inside the cell than outside the cell. This difference in concentration mean that K+ ions will leak out through potassium channels. This flow of K+ constitutes a current and the channel acts like a resistor. The movement of K+ through the membrane of your cells is determined by the electrical resistance of the membrane channels!

HERE are a few problems!!

Circuits!!

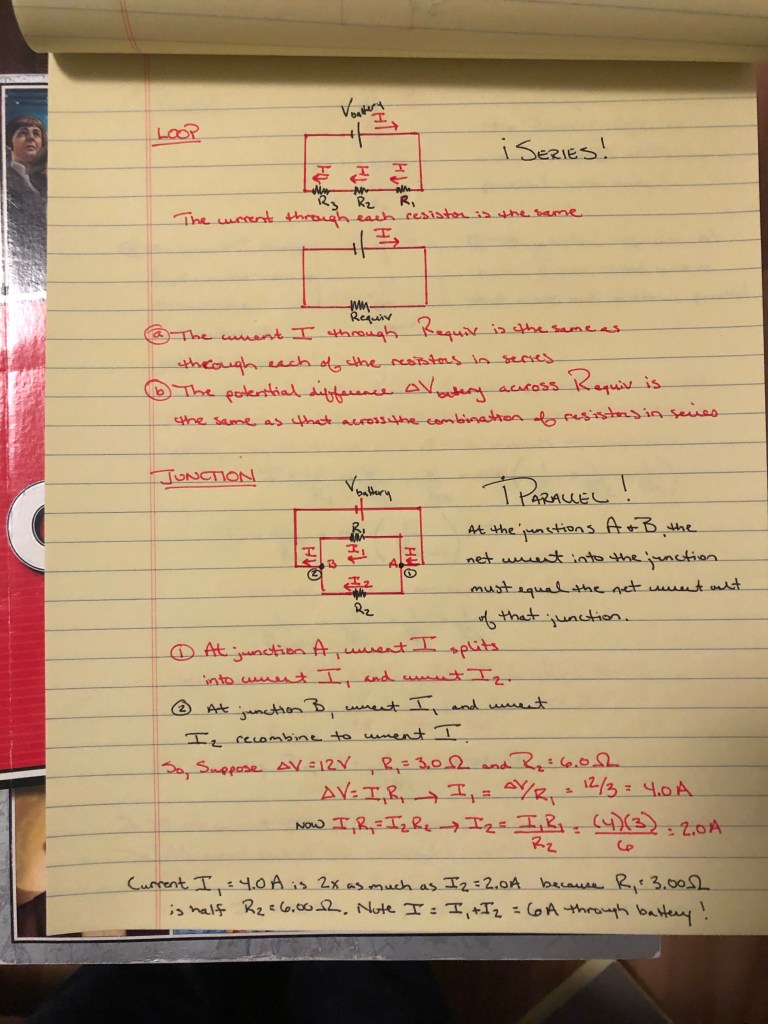

Once a current is established, the change in energy of a charge as it moves around a closed path must add to zero. And, as we learned, the electric potential difference is the change in energy per unit charge. This idea was first brought to bare by Prussian physicist, Gustav Kirchhoff and is called Kirchhoff’s Loop Rule:

The sum of the changes in potential around a closed loop in a circuit must equal zero.

An important application of The Loop Rule is to resisters in series, that is, resistors connected end to end. The total energy given to a charge as it moves through the battery must be equal to the energy it loses through the resistors, no matter the number of resistors. Let’s say we replace three resistors in a circuit with an equivalent resistance that gives the same current as the series combination. So, according to Ohm’s Law, the same current is present through each of the resistors and the total change in potential (V) across three resistors in series is the sum of the voltage differences.

IR(equiv) = IR(1) + IR(2) + IR(3)

…and this simplified to…

R(equiv) = R(1) + R(2) + R(3)

Combining resistors in series creates a circuit with a higher equivalent resistance than that of any individual resistor! Essentially we have made a longer resistor by placing resistors “end to end“. For resistors in series, the current is the same through each resistor but the change(V) is different for different resistors. (V = IR)

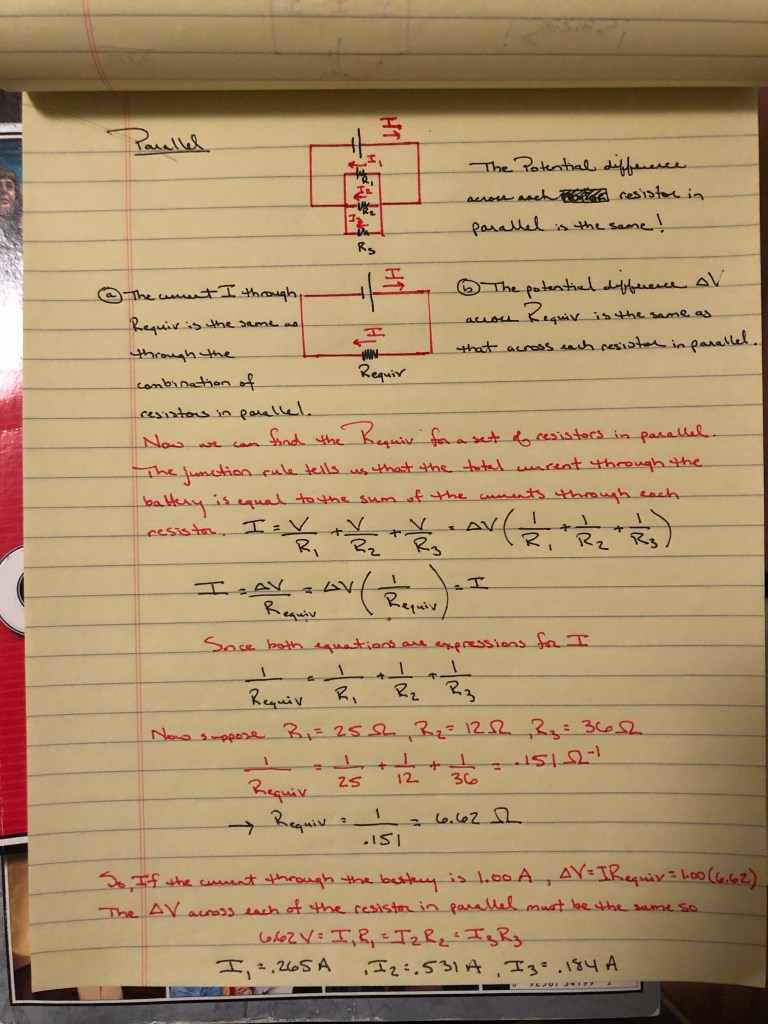

Unlike a single loop, resistors in parallel constitute a multi-loop circuit and make up most household circuits! There is more than one pathway that the moving charge can take through the circuit from the positive terminal to the negative terminal. In the example below, there are two two junctions where the currents either breaks or comes together. What is the relationship between current I that passes through the battery, I(1) that goes through R(1) and I(2) that goes through R(2)?

Well, since charge is always conserved, the current is conserved which means that charge can neither be created nor destroyed, nor pile up. The rate at which the current arrives at a junction must equal the rate at which the charge leaves the junction. This is Kirchhoff’s Junction Rule.

The sum of the currents into a junction equals the sum of the currents out of the junction.

Let’s apply the Junction Rule to the circuit below. The current I represents the flow of charge into Junction A and current I(1) and I(2) represent the charge flow out of it. Therefore, I = I(1) + I(2). At Junction B, the sum of the currents in is I(1) + I(2) and the sole current out is I. So if we look at each junction, I = I(1) + I(2). The currents divide and rejoin at junctions A & B, respectively!

This concept, neat for sure, doesn’t tell us how much of I takes the branch into R(1) as I(1) and how much takes the branch through resistor R(2) as I(2). To determine this, let’s apply the Loop Rule to two different loops!

First, consider the loop that starts at the negative terminal and travel through the battery to the positive terminal (electric potential increases by V(battery)) then follows I(1) through R(1) and the electric potential decreases by I(1)R(2) and returns to the negative terminal. From the loop, the net change in electric potential is zero so…

change(V(battery)) = I(1)R(1)

The second loop starts in the same manner and then follows the path of I(2) through R(2). Again the Loop Rule states that the net change is zero so…

change(V(battery)) = I(2)R(2)

These equations can only be true if

I(1)R(1) = I(2)R(2)

In other words, for resistors in parallel, the electric potential must be the same for each resistor. However, the currents are different for each resistor.

If R(1) is less than R(2) the current will be greater in R(1) and smaller in R(2).

So, as you can see, the current is greatest through R(2) which has the smallest of the the three resistances. So combining resistors in parallel creates a circuit with a smaller equivalent resistance than any of the individual resistors. We have, essentially, increased the cross-sectional area of the equivalent resistor!!

Power!!

The transfer of energy, like from the wall socket to your toaster or tea kettle is the most fundamental use of an electric circuit. And, we mostly are concerned with the rate at which this energy is transferred in or out of the circuit element. After all, we want our bagel in a minute or two, not an hour, am I right??

Power is the rate at which energy is transferred. Every single lightbulb is stamped with the amount of powers that must be supplied to it. So, with a current I in a circuit, the power P for each circuit element is simply the rate at which electric potential energy is converted by that element. So…

P = change(q)/change(t) x V

…or…

P = IV

And since V = IR

P = I^2R and P = V^2/R

So in it’s purest form, a household lightbulb is designed to be connected to the standard 120 V parallel circuit at Flynn Ave. as opposed to the 240 V parallel circuits on Abbey Rd. So assuming a supply of 120 each bulb is rated a different wattage. A 40 W bulb dissipates 40 W only if it is supplied with 120 V. A 100 W bulbs dissipates energy faster and thus the bulb is brighter!! Also, Burlington Electric charges us based not on the power we use but the total energy we use. Since P = change(E)/time, the units of Energy are the units of power multiplied by the unit of time. Hence we see Kilowatt(hours) on our bill!!

And HERE we have a few awesome problems!!

And THIS worksheet will be very helpful if you wanted to have some fun with it. It’s kind of like a puzzle.

…and finally here is the key to the worksheet above!! It is such a great exercise and so important to understanding circuits!!!